Image 1 of 3

Image 1 of 3

Image 2 of 3

Image 2 of 3

Image 3 of 3

Image 3 of 3

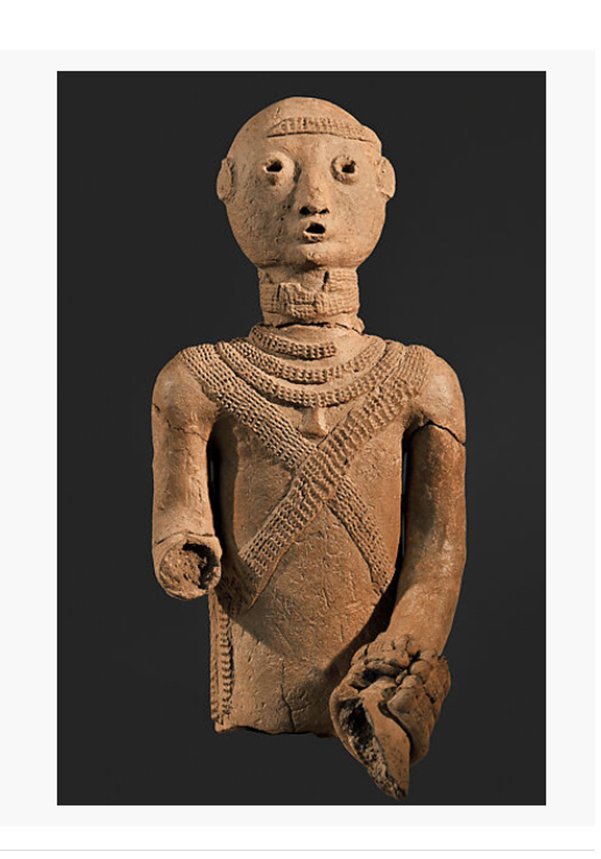

Bura terracotta figure

Bura peoples

Nigeria

3rd–11th century

H. 27,5 cm

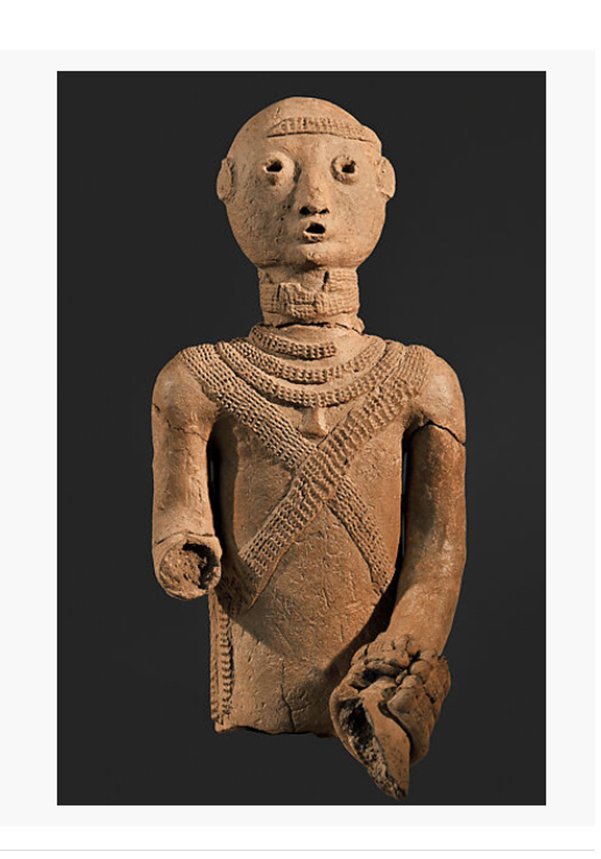

The Bura are a true paradox : almost nothing is known of this shadowy Nigerian/Malian group. They appear to have originated in the first half of the first millennium AD, although the only archaeologically-excavated site (Nyamey) dates between the 14th and 16th centuries. They are contemporary with – and probably related to – the Djenne Kingdom, the Koma, the Teneku and a satellite culture known as the Inland Niger Delta. Insofar as can be ascertained, the Bura share certain characteristics with these groups ; for our purposes, these include extensive ceramic and stone sculptural traditions.

The Bura appear to have been sedentary agriculturists who buried their dead in tall, conical urns, often surmounted by small figures. Their utilitarian vessels are usually plain, while other “containers” – the function of which is not understood – are often decorated with incised and stamped patterns. Their best-known art form is radically reductivist anthropomorphic stone statues, with heads rendered as squares, triangles and ovals, with the body suggested by a columnar, monolithic shape beneath. Phallic objects are also known ; some phallomorphic objects may have been staffs, perhaps regalia pertaining to leaders of Bura groups. Ceramic heads are usually more complex than their stone counterparts, with incised decoration and variable treatment of facial proportions and features. There are a few very rare equestrian figures, which bear some resemblance to Djenne pieces ; almost no intact human or equestrian figures are known.

The range of figures is so large that it presumably indicates differing geographical and temporal trends in aesthetics within the Bura polity. Equally, similar figures with different scarifications of coiffures could imply production by a range of different workshops or areas. However, without more complete contextual information it is impossible to explore this possibility, and it is necessary to glean what we can from the art itself.

The role of these figures is almost totally obscure. Equestrian figures probably represent high status individuals, and the very few full-body representations of humans may be portraits or ancestor figures. Intuitively – as with so many other groups both inside and beyond Africa – figures with exaggerated sexual characteristics would tend to be associated with fertility and fecundity, as would any artefact modelled in the shape of pudenda (although the sceptre-like qualities of some such pieces should be noted – see above). The distribution of decoration on some ceramic pieces (notably phalluses) may suggest that they were designed to be viewed from one angle only – perhaps as adorational pieces. This is true of decorated urns that have no obvious secular importance. Many pieces are believed to have been found in burials, perhaps implying an importance that would have been linked to social standing and status.

Bura peoples

Nigeria

3rd–11th century

H. 27,5 cm

The Bura are a true paradox : almost nothing is known of this shadowy Nigerian/Malian group. They appear to have originated in the first half of the first millennium AD, although the only archaeologically-excavated site (Nyamey) dates between the 14th and 16th centuries. They are contemporary with – and probably related to – the Djenne Kingdom, the Koma, the Teneku and a satellite culture known as the Inland Niger Delta. Insofar as can be ascertained, the Bura share certain characteristics with these groups ; for our purposes, these include extensive ceramic and stone sculptural traditions.

The Bura appear to have been sedentary agriculturists who buried their dead in tall, conical urns, often surmounted by small figures. Their utilitarian vessels are usually plain, while other “containers” – the function of which is not understood – are often decorated with incised and stamped patterns. Their best-known art form is radically reductivist anthropomorphic stone statues, with heads rendered as squares, triangles and ovals, with the body suggested by a columnar, monolithic shape beneath. Phallic objects are also known ; some phallomorphic objects may have been staffs, perhaps regalia pertaining to leaders of Bura groups. Ceramic heads are usually more complex than their stone counterparts, with incised decoration and variable treatment of facial proportions and features. There are a few very rare equestrian figures, which bear some resemblance to Djenne pieces ; almost no intact human or equestrian figures are known.

The range of figures is so large that it presumably indicates differing geographical and temporal trends in aesthetics within the Bura polity. Equally, similar figures with different scarifications of coiffures could imply production by a range of different workshops or areas. However, without more complete contextual information it is impossible to explore this possibility, and it is necessary to glean what we can from the art itself.

The role of these figures is almost totally obscure. Equestrian figures probably represent high status individuals, and the very few full-body representations of humans may be portraits or ancestor figures. Intuitively – as with so many other groups both inside and beyond Africa – figures with exaggerated sexual characteristics would tend to be associated with fertility and fecundity, as would any artefact modelled in the shape of pudenda (although the sceptre-like qualities of some such pieces should be noted – see above). The distribution of decoration on some ceramic pieces (notably phalluses) may suggest that they were designed to be viewed from one angle only – perhaps as adorational pieces. This is true of decorated urns that have no obvious secular importance. Many pieces are believed to have been found in burials, perhaps implying an importance that would have been linked to social standing and status.